“Even if a litter of coy-dog pups is successfully reared by the mother alone, these hybrids must later face still-greater obstacles…”

— Hope Ryden, God’s Dog

There’s something quietly powerful about the way Mother Nature watches over the coyote.

Though domestic dogs and coyotes can sometimes mate, nature steps in — with timing, instinct, and biology — to gently hold the coyote’s wildness in place.

It’s not rigid or aggressive.

It’s simply designed that way.

A Matter of Timing

Coyotes follow a different rhythm than domestic dogs.

They breed only once a year, in late winter — a natural clock set by the land itself.

Dogs, on the other hand, can mate at any time.

So while a pairing between a male dog and a female coyote is possible, it’s rare.

And what happens next is even more interesting.

Hope Ryden’s Wisdom on Coy-Dogs

In her beautiful and thorough book God’s Dog, author and naturalist Hope Ryden explains how hybrid offspring — called coy-dogs — quickly lose their connection to the wild.

“Both male and female coy-dogs come into heat in the fall, three to four months earlier than do pureblood coyotes. Thus, they can never mate back to the wild side of their family.”

In other words, they’re out of sync.

Their internal calendar doesn’t match that of wild coyotes —

so they can’t pass their genes back into the coyote world.

And Then Comes Winter…

Even if coy-dogs do find mates, their litters are born in the middle of winter —

the hardest time of year for pups to survive.

“Any issue born to it must meet life during the harshest time of year, in midwinter, and the prospect of such an unfortunate litter surviving under wild conditions are poor indeed.”

Unlike coyotes, who raise their young as a pair, male coy-dogs tend to follow their domestic lineage — they don’t help care for the pups.

So the mother is left alone, in deep winter, with little chance of feeding or protecting her young.

“It is doubtful, therefore, that a coy-dog female can, by herself, find sufficient food during the winter months to nurse and feed a litter.”

What Does This Mean?

It means that over time, Mother Nature quietly prevents hybridization.

Not through force — but through timing.

Through seasons.

Through the instincts written into every heartbeat.

Coyotes remain wild not because they resist change…

but because they are already perfectly adapted to their place in the world.

“It is unlikely that a race of wild coy-dogs has arisen or ever will arise,”

Ryden concludes.

Something to Marvel At

Rather than fearing “mongrelization,” or trying to interfere with wild populations, we might simply pause and admire the subtle brilliance of nature’s system.

Coyotes aren’t broken.

They don’t need reshaping.

They already belong — exactly as they are.

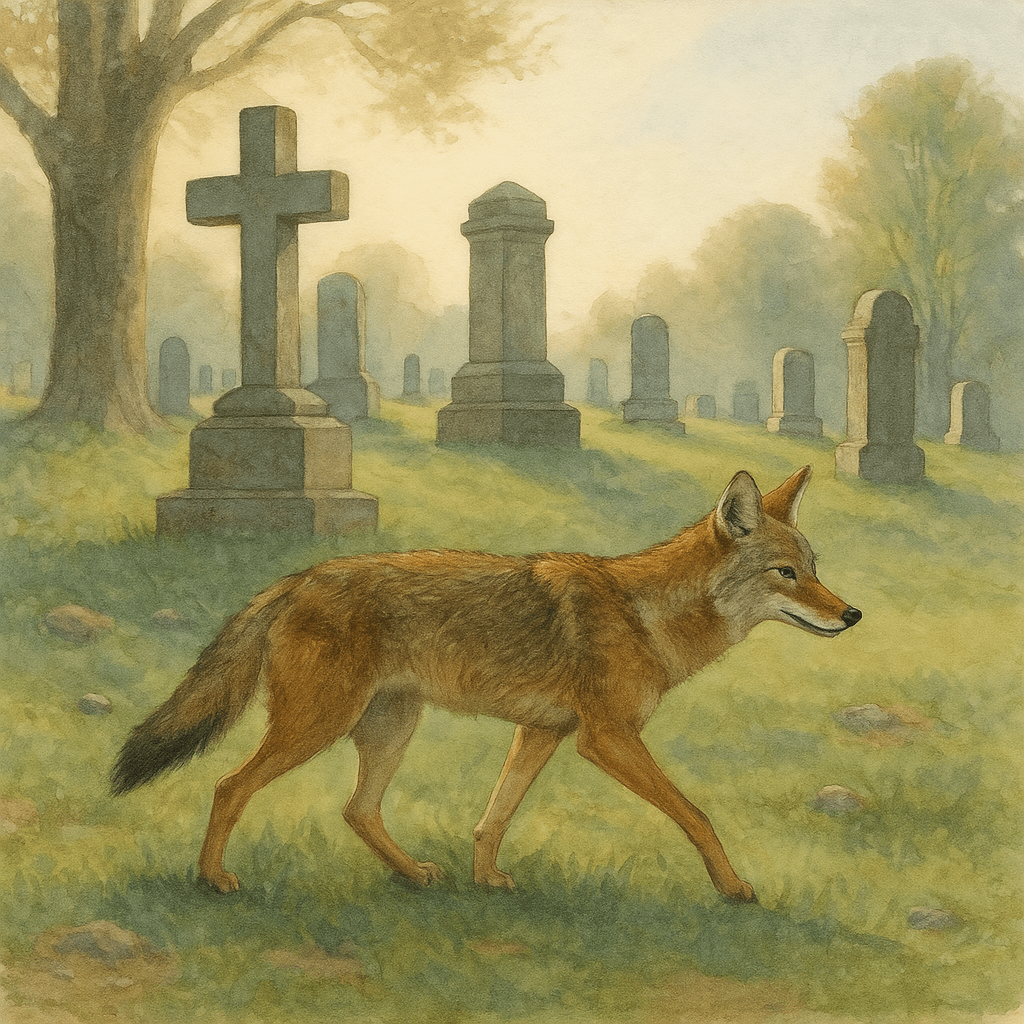

What About Black Coyotes?

If coyotes are so protected by Nature, you might wonder — what about the black ones?

Like Carmine, the striking black coyote seen in urban and forested landscapes — where did he get his rare coat?

The answer is both surprising and beautiful.

Black coyotes carry a genetic mutation that originally came from domestic dogs.

Scientists believe the black coat gene — a variation on the K locus — was introduced into the coyote population thousands of years ago, likely through early contact with Indigenous dogs in North America.

But here’s where Nature steps in again.

Instead of allowing the entire coyote species to change, Mother Nature selected for the black coat only in places where it helped them survive — in wooded environments, where dark fur offers camouflage and better hunting advantage.

So yes — the origin of the black coat is domestic.

But its presence today? That’s natural selection at work.

Coyotes like Carmine are still wild, still part of the songdog lineage —

they just carry a mark of something ancient.

A soft echo of a one-time crossing.

A reminder that even when genes mix, Nature decides what stays.

Is Carmine Really a Coyote?

Yes — DNA testing at Yellow River Wildlife Sanctuary confirmed that Carmine is 100% coyote.

Though some people question his black coat, it’s important to know that black coyotes are naturally occurring, especially in places like North Carolina, parts of the southeastern U.S., and other warmer forested regions.

The black coat comes from a recessive gene (on the K locus) that was introduced long ago through ancient contact with domestic dogs. But over generations, this gene became part of the natural coyote population and is now selected for in certain environments, especially where dark fur offers better camouflage.

So while the origin of the coat color may be ancient, Carmine’s spirit, genetics, and behavior remain fully wild.

His appearance may challenge expectations —

but his essence is pure songdog.

🐺